A behavioral scientist

By Rick Kahler MS CFP®

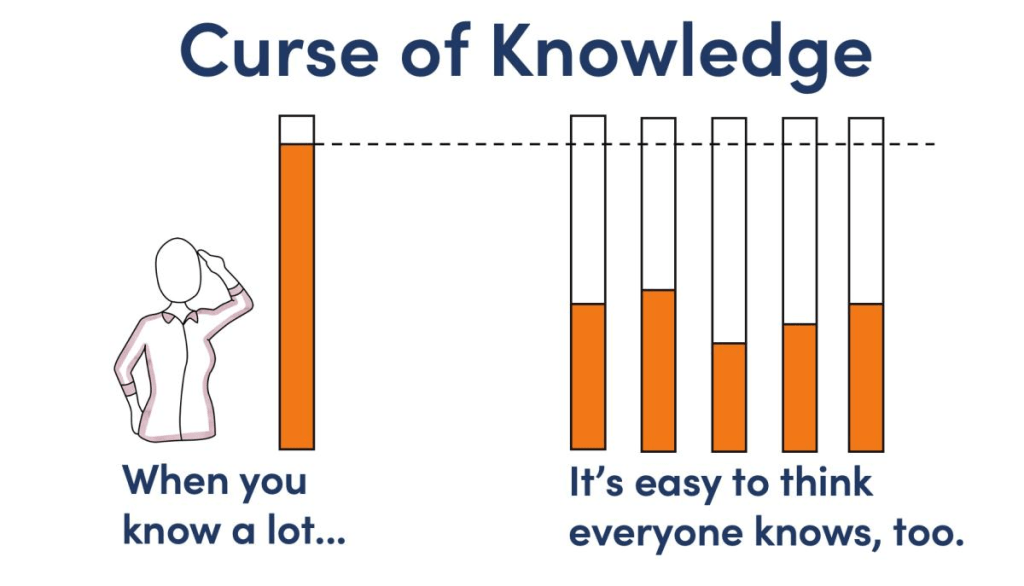

Human beings make most of our decisions—including financial ones—emotionally, not logically. Unfortunately, too much of the time, our emotions lead us into financial choices that aren’t good for our financial well-being. This is hardly news to financial planners or financial therapists. Nor is it a surprise to any parent who has ever struggled to teach kids how to manage money wisely.

Economic Model Assumptions

Yet many of the economic models and theories related to investing are based on assumptions that, when it comes to money, people act rationally and in their own best interests. There’s a wide gulf between the way economists assume people behave around money and the way people actually make money choices. This doesn’t encourage financial advisors to rely on what economists say about financial patterns, trends, and what to expect from markets or consumers.

2017 Nobel Prize in Economics

It’s significant, then, that the 2017 Nobel Prize in Economics went to Dr. Richard H. Thaler, professor of behavioral science and economics at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Dr. Thaler’s work has focused on the differences between logical economic assumptions and real-world human behavior. His research not only demonstrates that people behave emotionally when it comes to money; it also shows that in many ways our irrational economic behavior is predictable.

This predictability can help advisors and organizations find ways to encourage people to make financial decisions in their own better interest. The book Nudge, by Dr. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein, describes some of those methods.

Example:

One example is making participation the default option for company retirement programs like 401(k)’s. Employees are free to opt out, of course, but they need to actively choose to do so.

A second example is the “Save More Tomorrow” plan, which offers employees the option of automatically increasing their savings whenever they receive raises in the future.

Both of these examples rely on a predictable behavior—human inertia. Most of us tend to postpone, ignore, or forget to take action even when that action would be good for us. So if a system is set up so not taking action leaves us with the choice that serves us better, we are “nudged” toward helping ourselves toward a healthier financial future.

Integration

As one of the pioneers in integrating the emotional aspect of money behavior into the practice of financial planning, I’ve long since come to understand that managing money is about much more than numbers. The world of investing may seem to be cold and calculating, but it’s actually driven by emotions. I’m familiar with the work of researchers who have demonstrated that some 90% of all financial decisions are made emotionally rather than logically.

I was pleased in 2002 when one of those researchers, psychologist Daniel Kahneman, won the Nobel prize in economics for his studies of human behavioral biases and systematic irrational behaviors. (That research was done jointly with psychologist Amos Tversky, who died in 1996.)

I’m even more pleased to see the economics Nobel prize go to a behavioral researcher for the second time. Maybe the realm of economics is beginning to integrate the untidy realities of human emotions into its theories. Eventually, this might lead to new economic models that take into account the emotions that shape people’s money decisions and the fact that money is one of the most emotionally charged aspects of our lives.

Assessment

Perhaps economists are beginning to appreciate the truth of the statement Dr. Thaler made at a news conference after his prize was announced. “In order to do good economics, you have to keep in mind that people are human.”

Conclusion

Your thoughts and comments on this ME-P are appreciated. Feel free to review our top-left column, and top-right sidebar materials, links, urls and related websites, too. Then, subscribe to the ME-P. It is fast, free and secure.

Speaker: If you need a moderator or speaker for an upcoming event, Dr. David E. Marcinko; MBA – Publisher-in-Chief of the Medical Executive-Post – is available for seminar or speaking engagements.

EDITOR

Contact: MarcinkoAdvisors@msn.com

Subscribe: MEDICAL EXECUTIVE POST for curated news, essays, opinions and analysis from the public health, economics, finance, marketing, I.T, business and policy management ecosystem.

***

Filed under: "Ask-an-Advisor", Ethics, Experts Invited, iMBA, Inc., Investing, LifeStyle | Tagged: Amos Tversky, behavioral economics, Daniel Kahneman, psychology, Richard H. Thaler, Rick Kahler MS CFP® | 4 Comments »