A.I. by Artificial Intelligence

***

***

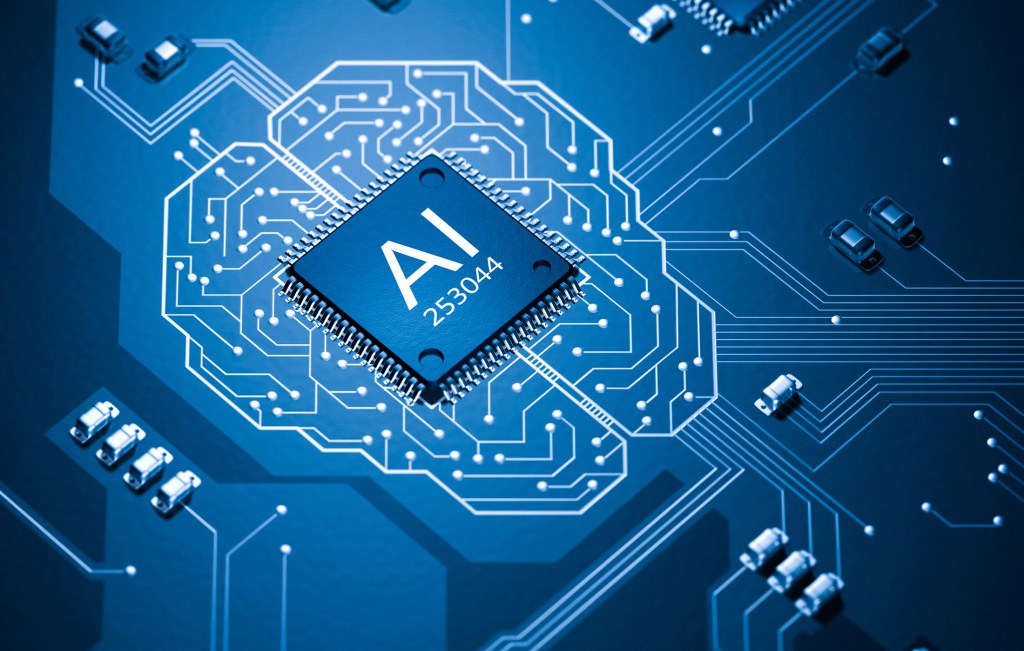

Artificial intelligence (AI) refers to computer systems capable of performing complex tasks that historically only humans could do, such as reasoning, making decisions, or solving problems. Today, the term “AI” describes a wide range of technologies that power many of the services and goods we use every day – from apps that recommend TV shows to chatbots that provide customer support in real time. And yet, there is a hierarchy among related concepts such as machine learning and deep learning.

So, to summarize the hierarchy:

- AI is the goal: machines that can think and act intelligently.

- Machine learning is a method within AI that lets machines learn from data.

- Deep learning is a specialized form of machine learning that uses multi-layered neural networks to analyze data in a way that mimics the human brain.

It’s a feature, not a bug

And, there’s no shortage of companies leveraging AI today to remain profitable, to the delight of Salesforce investors: among others:

- Wells Fargo’s CEO has touted trimming its workforce for 20 straight quarters. Its stock is up 228% over the past five years.

- Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan wasn’t hiding it during a recent earnings call when he said the company has let go of 88,000 employees over the past 15 years. BofA stock is up 95% since 2020.

- Amazon, with its share value up 28% over the past year, recently told staff that AI implementation would lead to layoffs.

- Microsoft has cut 15,000 jobs in the past two months as the company pivots to AI—and its stock is also up since the beginning of July.

COMMENTS APPRECIATED

Like, Refer and Subscribe

***

***

Filed under: "Ask-an-Advisor", business, finance, Information Technology, Investing, Portfolio Management | Tagged: AI, AI profits, Amazon, artificial intelligence, Bank America, BoA, Brian Moynihan, microsoft, Salesforce, stock, stocks rises, Wells Fargo | Leave a comment »