By Staff Reporters

***

***

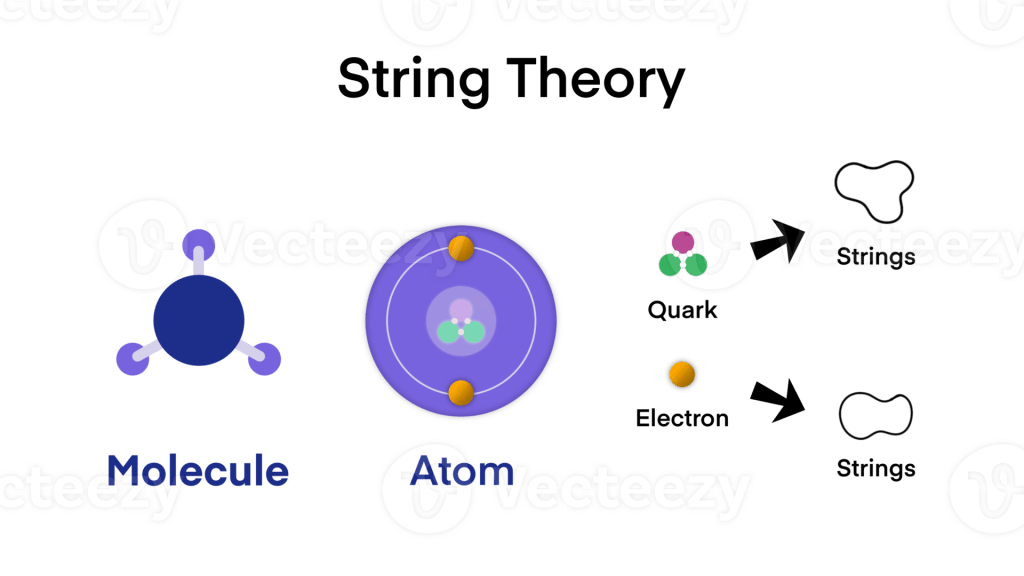

String theory stands as one of the most ambitious and mathematically intricate attempts to understand the fundamental nature of reality. Emerging from the crossroads of quantum mechanics and general relativity, string theory proposes a radical reimagining of the universe’s building blocks—not as point-like particles, but as tiny, vibrating strings. These strings, though unimaginably small, may hold the key to a unified theory of everything.

Origins and Motivation

The origins of string theory trace back to the late 1960s, when physicists sought to explain the strong nuclear force. Initially, string theory was considered a candidate for modeling hadrons, but it was soon overshadowed by quantum chromodynamics. However, the theory’s mathematical structure revealed properties that made it a promising framework for quantum gravity—a domain where traditional physics struggled to reconcile Einstein’s general relativity with quantum mechanics.

Einstein’s theory of general relativity describes gravity as the curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy, while quantum mechanics governs the behavior of particles at the smallest scales. These two pillars of modern physics, though individually successful, are fundamentally incompatible. String theory offers a potential bridge between them, suggesting that all particles and forces arise from different vibrational modes of one-dimensional strings.

Core Concepts

At its heart, string theory replaces point particles with strings—tiny filaments that can be open or closed loops. The way a string vibrates determines the properties of the particle it represents, such as mass and charge. For instance, one vibrational pattern might correspond to an electron, while another might represent a photon.

A striking implication of string theory is the necessity of extra dimensions. While we perceive the universe in three spatial dimensions and one time dimension, string theory requires up to ten spatial dimensions and one time dimension for mathematical consistency. These extra dimensions are thought to be compactified—curled up so tightly that they are imperceptible at human scales. The geometry of these compactified dimensions, often modeled as Calabi-Yau manifolds, influences the physical laws we observe.

Another cornerstone of string theory is supersymmetry, a theoretical symmetry that links bosons (force-carrying particles) and fermions (matter particles). Supersymmetry predicts that every known particle has a heavier superpartner, though none have yet been observed experimentally. If confirmed, supersymmetry could solve several puzzles in particle physics, including the hierarchy problem and the nature of dark matter.

Applications and Implications

Beyond its quest for unification, string theory has influenced numerous areas of physics and mathematics. It has provided insights into black hole entropy, suggesting that the information content of a black hole can be accounted for by stringy degrees of freedom. The AdS/CFT correspondence, a conjecture arising from string theory, links a gravitational theory in a higher-dimensional space (Anti-de Sitter space) to a conformal field theory on its boundary. This duality has found applications in quantum field theory, condensed matter physics, and even quantum computing

Versions and Unification

Over time, physicists developed five consistent versions of string theory: Type I, Type IIA, Type IIB, and two heterotic string theories. In the mid-1990s, Edward Witten and others proposed that these seemingly distinct theories were actually different aspects of a single, more fundamental theory known as M-theory. M-theory posits eleven dimensions and includes higher-dimensional objects called branes, to which strings can attach. This unification marked a major milestone in theoretical physics and sparked renewed interest in string theory.

Criticisms and Challenges

Despite its elegance and potential, string theory faces significant challenges. Foremost among them is the lack of experimental evidence. The energy scales at which stringy effects become apparent are far beyond the reach of current particle accelerators. Moreover, the theory’s vast landscape of possible solutions—estimated to be on the order of 10^500—makes it difficult to extract unique predictions about our universe.

Critics argue that string theory’s reliance on unobservable dimensions and its resistance to empirical testing place it outside the realm of conventional science. Others contend that its mathematical beauty and internal consistency justify continued exploration, even in the absence of direct evidence.

Conclusion

String theory represents a bold and imaginative attempt to unify the forces of nature and reveal the deepest truths of the cosmos. While its experimental validation remains elusive, its impact on theoretical physics and mathematics is undeniable. Whether it ultimately proves to be the “theory of everything” or a stepping stone to a deeper understanding, string theory continues to inspire scientists to look beyond the visible and explore the hidden dimensions of reality.

COMMENTS APPRECIATED

Like, Refer and Subscribe

***

***

Filed under: Ask a Doctor, Glossary Terms, Research & Development | Tagged: albert einstein, atoms, black holes, cosmos, fermions, hadron collider, neutrons, protoens, quarks, string theory, strings, supersymmetry |

Leave a comment