SPONSOR: http://www.CertifiedMedicalPlanner.org

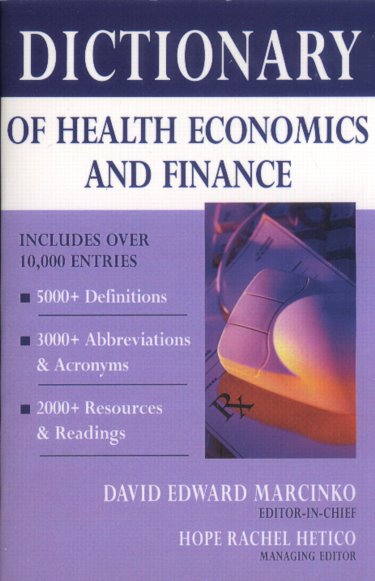

Dr. David Edward Marcinko MBA MEd

***

***

Affinity marketing has emerged as a powerful strategy in the financial services industry, particularly among investment advisors seeking to build trust, expand their client base, and differentiate themselves in a competitive marketplace. At its core, affinity marketing involves forming partnerships or aligning with organizations, communities, or groups that share common interests, values, or identities. By leveraging these connections, investment advisors can create a sense of belonging and credibility that traditional advertising often struggles to achieve. This essay explores how investment advisors use affinity marketing, the benefits it provides, and the challenges it presents.

Understanding Affinity Marketing

Affinity marketing is based on the principle that individuals are more likely to engage with businesses endorsed by groups they already trust. For investment advisors, this often means collaborating with professional associations, alumni networks, religious organizations, or niche communities. Instead of approaching potential clients cold, advisors gain access to audiences who already feel a sense of loyalty to the group. The advisor’s association with that group signals shared values and reduces skepticism, making it easier to initiate conversations about financial planning and investment management.

Building Trust Through Shared Identity

Trust is the cornerstone of financial advising, and affinity marketing provides a shortcut to establishing it. When an advisor partners with a respected organization, members of that group perceive the advisor as vetted and credible. For example, an advisor who works closely with a medical association can position themselves as a specialist in serving physicians. The shared identity—whether professional, cultural, or religious—creates a bond that reassures clients that the advisor understands their unique needs and challenges. This sense of familiarity often translates into stronger client relationships and higher retention rates.

Tailoring Services to Niche Markets

Affinity marketing also allows investment advisors to tailor their services to specific niches. Advisors who focus on educators, for instance, can design retirement planning strategies that account for pension systems and tenure considerations. Those who serve small business owners can emphasize succession planning and tax-efficient investment structures. By narrowing their focus, advisors not only demonstrate expertise but also create marketing messages that resonate deeply with their chosen audience. This specialization enhances the advisor’s reputation and makes them the go-to resource within that community.

Expanding Reach Through Partnerships

Partnerships are a central mechanism of affinity marketing. Investment advisors often collaborate with organizations to offer seminars, workshops, or educational content. These events provide value to the group while positioning the advisor as a trusted expert. Advisors may also sponsor community activities, contribute to newsletters, or provide exclusive benefits to members. Such involvement increases visibility and fosters goodwill, ensuring that when members think about financial guidance, the advisor’s name comes to mind. Importantly, these partnerships often generate referrals, as satisfied clients recommend the advisor to others within the same affinity group.

Emotional Connection and Client Loyalty

Beyond practical benefits, affinity marketing taps into the emotional dimension of client relationships. People prefer to work with advisors who “get them,” who understand not only their financial goals but also their values and lifestyle. By aligning with affinity groups, advisors demonstrate cultural competence and empathy. This emotional connection strengthens loyalty, making clients less likely to switch advisors even when presented with competing offers. In an industry where client retention is as important as acquisition, this loyalty is invaluable.

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

Despite its advantages, affinity marketing is not without challenges. Advisors must ensure that their partnerships are genuine and not exploitative. Clients may feel misled if they perceive the advisor as using the group merely as a marketing tactic rather than truly understanding its members. Advisors also face regulatory scrutiny, as financial services are heavily regulated and partnerships must comply with disclosure requirements. Transparency is essential to maintain trust. Additionally, focusing too narrowly on one affinity group can limit growth opportunities, so advisors must balance specialization with diversification.

***

***

The Future of Affinity Marketing in Financial Services

As technology reshapes the financial industry, affinity marketing is likely to evolve. Online communities, social media groups, and digital platforms provide new avenues for advisors to connect with like-minded individuals. Virtual seminars and targeted digital campaigns can replicate the intimacy of traditional affinity marketing while reaching broader audiences. Advisors who embrace these tools will be able to scale their efforts without losing the personal touch that makes affinity marketing effective.

Conclusion

Affinity marketing offers investment advisors a powerful way to build trust, establish credibility, and deepen client relationships. By aligning with groups that share common identities or values, advisors can differentiate themselves in a crowded marketplace and create lasting emotional connections with clients. While challenges exist, particularly around authenticity and compliance, the benefits of affinity marketing—stronger trust, tailored services, and loyal clients—make it an enduring strategy. As the financial services industry continues to evolve, investment advisors who skillfully employ affinity marketing will remain well-positioned to thrive.

COMMENTS APPRECIATED

SPEAKING: Dr. Marcinko will be speaking and lecturing, signing and opining, teaching and preaching, storming and performing at many locations throughout the USA this year! His tour of witty and serious pontifications may be scheduled on a planned or ad-hoc basis; for public or private meetings and gatherings; formally, informally, or over lunch or dinner. All medical societies, financial advisory firms or Broker-Dealers are encouraged to submit an RFP for speaking engagements: CONTACT: Ann Miller RN MHA at MarcinkoAdvisors@outlook.com -OR- http://www.MarcinkoAssociates.com

Like, Refer and Subscribe

***

***

Filed under: iMBA, Inc. | Tagged: david marcinko | Leave a comment »